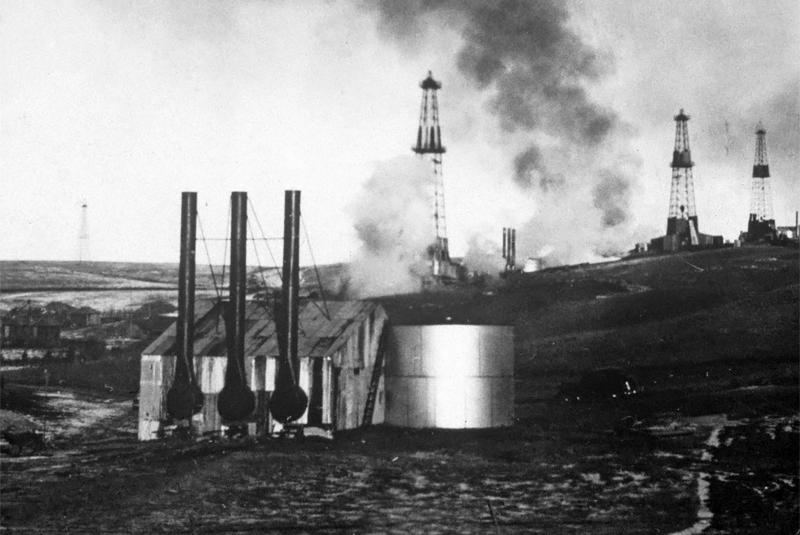

Once upon a time, in the first part of the 20th century around a southern Alberta town, an industry was born. Turner Valley quickly became synonymous with the province’s first oil boom, attracting capital from investors hungry for easy money. But that easy money came at the price of the wasteful practice of flaring off “worthless” natural gas in the pursuit of valuable black gold. The name Turner Valley is also known for spawning Alberta’s first oil and gas regulator, charged with protecting the province’s energy resources.

The following is an excerpt from Steward, a book published by the AER’s predecessor, the Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB), to mark 75 years of energy regulation in Alberta. This is part 1 of a two-part telling of what led to the creation of energy regulation in Alberta. Watch for part 2 in the new year.

You could tell in the Valley where somebody was showing off for promoters. You could see the smoke rings. They were very noticeable — beautiful.

Bert Corey, well operating contractor

The oil coming out of … early Turner Valley wells was a light liquid known as naphtha, condensate, or natural gasoline. Pure enough to burn in automobiles without refining, naphtha was more valuable at the time than the natural gas that spewed out in even greater quantities along with it. … Calgary, 50 kilometres north of the field, had just 55 000 residents at the time of the 1914 discovery. They were served by a pipeline completed in 1912 from a 1909 gas find called Old Glory, 240 kilometres southeast of the city at Bow Island.

The second Turner Valley discovery in 1924 greatly exceeded the additional capacity required by a population that was growing but still only 65 000. At the time, Calgary gas consumption averaged 20 million cubic feet per day, peaking at 70 million on the coldest winter days. That’s less than one-tenth of the estimated daily average of 500 – 600 million cubic feet per day flared into the sky at Turner Valley as industrial waste.

Even today, storing a resource as volatile as gas for later use involves an expensive array of airtight hardware, managed underground rock formations, and injection and extraction wells. Given those realities, the oil men equipped Turner Valley with a separator to strip out and capture the naphtha and flared off most of the gas. …

… “I didn’t know what it was to sleep in the dark for many years,” said Chuck Moore, who grew up and worked in 1920s and ’30s Turner Valley. “We had these yellow blinds. With the blind pulled you could read a newspaper or a book.” The flares were so big and bright that they posed a night-driving hazard, he added. “You’d have a heck of a time staying on the road. Sometimes you’d have to stick your head out the window to see past the reflections on the windshield.” Moore blamed the flares for a road accident that killed one friend and badly injured another.

“It was quite a show place for tourists,” recalled J. Grant Spratt, a geologist whose career included roles in both the federal and provincial governments as well as in industry. “Almost every night there was that great red glare in the skies. People would go out visiting it from Calgary and eastern Canada and the United States.” From a distance, the effect at night could be as striking as the first daytime glimpse of the Rocky Mountains to travelers crossing Canada from east to west. “The first airplanes that came through here used Turner Valley to get their beam for Calgary,” Spratt said. As far away as Medicine Hat, 267 kilometres southeast of the city, “they could see the reflection of the flares in the skies.”

Promoters used Turner Valley as a hard-sell form of investor relations, said Bert Corey, who took part in the antics after leaving the ERCB to be a well operating contractor. His customers included renowned masters of the oil game such as brothers Frank and George McMahon, whose family name is immortalized on Calgary’s football stadium.

“George McMahon would come out with prospective investors and he would say, ‘Bert, would you come with us today out to one of the wells.’ And I’d say, ‘Sure, come on.’ And he’d say, ‘Now I want to impress these people. Would you just tell these separator operators to cock the well open?’ And I’d say ‘okay’ and go over and tip the guy off. And all of a sudden he’d open up the valve as wide as it would go. There’d be a huge roar. Smoke and gas would come out of the flare pit. Invariably there’d be a huge smoke ring. It would float up into the sky. You could tell in the Valley where somebody was showing off for promoters. You could see the smoke rings. They were very noticeable — beautiful. The investors thought this was outstanding, and it was.”

Early oil kings made no apologies for such behaviour. “The promoters, they are a necessary evil,” Corey said. “In most endeavours you have to get somebody that sells other people on the merits of a particular enterprise or an operation or an opportunity. These are the people who are the salesmen. They are a catalyst between the raw land, the finances, and the people — whatever you will — to get this group together so that you could get the business going and wells drilled. The promoter was the one that found the money and of course took the grief when an operation failed.”

Wasteful stunts were no loss from a commercial point of view. By the late 1920s, the Turner Valley glut drove gas down to eight cents per thousand cubic feet — and that was after extracting impurities such as sulphur for use in furnaces and stoves. ... Raw gas at wellheads fetched two cents, barely enough to cover processing fees, if that. For producers, the value of gas was at best zero or at worst a penalty lopped off their oil income, which hovered around $1.25 a barrel in 1938 ($19.58 in today’s loonies).

Resource Editor